By Jessica Nicholson

We are only recently, in the last few decades, accepting scientific considerations, evidence, and common sense that other animals are aware, experiencing beings and ultimately value their own lives. Simultaneously, we have seen an overall 60% decline in free living vertebrate populations and are forcing ever more animals into domesicration and “farms” for slaughter.

Ecosocialism is a movement that analyzes how economic and political forces can drive destruction of the earth’s ecosystem. It demands an end to the profit-driven capitalist system and an overarching understanding of connections between environmental justice, anti-imperialism and working class struggles. While ecosocialism is conscious of the interconnectedness of human conflicts, what is often overlooked are the institutionalized, wide-scale violence inflicted on nonhuman animals under this same system.

Our current ecological and social movements cannot be revolutionary if they don’t consider the problems of ownership and commodification of the other non-human individuals who share the world with us. We owe these individuals respect, but instead we’ve relegated them to the status of resource and property.

This is a call for equal consideration of other animals into our larger moral obligations towards justice, for acknowledgement of their rights as sentient beings, for their entitlement to protection, a life free from exploitation and being used as “resources” or “commodities” for human ends. It is a necessity to recognize their existence as having meaning of their own, separate from their utility to humans. We must demand a dismantling of the capitalist-patriarchy and move towards a more ecological, eco-social relationship with one another who share this planet with us. It’s time to adopt such inclusive ecosocialist ideals.

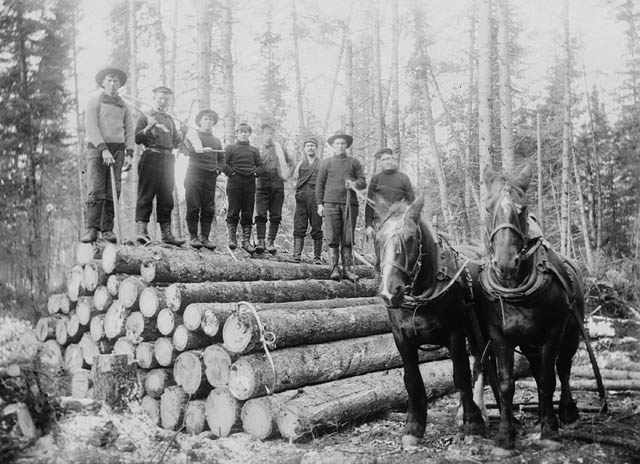

Depiction of horse exploitation. Canada’s major industry in terms of value of the product was the timber trade (Ontario, 1900 circa).

Vintage depiction of animal exploitation (“Pork Packaging in Cincinnati,” Public Domain)

Early appropriation of animals — the “snowball effect”

For a great majority still, liberation for non-human animals alongside the liberation of human animals comes off as an extreme ideal. It is absurd, for most, to return to other animals the right to not be owned, bought, separated, deprived, forced, impregnated, objectified, and killed for the use of a “superior” species. However, other animals have not always been under our control. It wasn’t until around 10,000 years ago that we began subjecting goats, cows and sheeps to enslavement, calling it “domestication.” The use and thus suffering of other animals is presented as a positive narrative in the history of our human-centered advancement. Utilizing animal labor power, sensory abilities and their very bodies to develop and elevate our own living standards and privileges (in true supremacist fashion) without considering the stories, needs, desires, and very lives of those whose backs—and flesh—these standards and privileges were built upon.

The majority of human civilization would not have made it so far in monopolizing the world and its ecosystems had it not forcefully employed other animals to do hard labor for human benefit and then be sold, dined upon, and tested on in the name of science. The narrative of “domestication” can either be told as a sugar-coated mutually beneficial agreement between the human species and others or as the oppressive story of unwilling “participants” who are deprived of freedom, life and autonomy. Which narrative would allow the continuation of capitalizing on animal labor? Scholars like David Nilbert combat the hand-in-hand, “mutual agreement” between the human species and other animals. Nilbert rejects usage of the word “domestication” arguing that it sanitizes and normalizes violence against animals. Because animals are desecrated in the process of what we call “domestication,” he coined the word “domesicration” as a replacement.

The majority of human civilization would not have made it so far in monopolizing the world and its ecosystems had it not forcefully employed other animals to do hard labor for human benefit and then be sold, dined upon, and tested on in the name of science. The narrative of “domestication” can either be told as a sugar-coated mutually beneficial agreement between the human species and others or as the oppressive story of unwilling “participants” who are deprived of freedom, life and autonomy. Which narrative would allow the continuation of capitalizing on animal labor?

In his book Animal Oppression and Human Violence: Domesecration, Capitalism and Global Conflict, he argues that the much-touted notion of a “natural partnership” between humans and “domesticated” animals is an “ideological construct that supports the status quo” used to promote advancement of human society and “masks the reality of a history deeply steeped in violence and deprivation.”

“While specific circumstances varied from case to case,” states Nilbert, “the exploitation of large groups of domesecrated animals throughout the centuries has resulted in deadly violence; displacement; enslavement or exploitation of the labor of the displaced; deaths from disease brought on by domesecration, hunger, and malnutrition; impoverishment; marginalization; and, frequently sexual exploitation. While the oppression of domesecrated animals certainly is not directly connected to all human conflict and violence, the death and destruction enabled and promoted by this practice has been monumental; such oppression certainly played a major, if not a pivotal, role in the emergence and expansion of capitalism and the predatory quests for profits that fueled domesecration-related violence over the past four hundred years.”

From the time that humankind decided to place ownership upon the free living animals that will become our current “farmed” animals — a practice first established across Eurasia towards the end of the Late Pleistocene era— the narrative that it is “human nature” to dominate and devour every last bit and inhabitant of our planet has been entrenched in our conscious and social structures. Following this narrative further supports a tyrannical rule over the planet and other inhabitants and has brought us to the ecological and moral dilemmas that we face in urgency. The same story of patriarchal governance led to the expansion of the feudal economic system by the 15th and 16th century. The development of feudalism was characterized by dominance of agriculture including the domesecration of animals that eventually led to the emergence of capitalism in the 17th century.

The links between Karl Marx’s primitive accumulation and colonialism, imperialism and human enslavement have been extensively researched. However, hardly is the emphasis made that animal agriculture was one of the main incentives of the enclosure of land. The relentless search for more pasture, feed-crop land, fresh water, and the collection of more domesecrated animals, were the reasons elites needed to consolidate the common lands and uproot sustenance based villages and societies. The elites then had native members of other lands (human and non-human animals) removed because they posed a threat to their own “resources” in Europe and to make room for their imported domesecrated animals and the empires that “process” them.

In the 18th century, saladero industries used the domesicration and killing of animals to produce dried “salt-meat” which were then exported to feed enslaved humans in Cuba and Brazil. The enslavement and consumption of other animals made it not only possible but profitable to cross the seas and wage violent pillages and wars against other devalued peoples and species to build empires by abusing the labor and bodies of one oppressed group back to another.

“The development of industrialized society under nineteenth-century capitalism, a process controlled by elite groups and driven by avarice, brought violence and oppression throughout the world—and much of the aggression was enabled by domesecration.” writes Nilbert, “Britain’s ascendency as the major world power in the nineteenth-century was advanced by its earlier colonization and deadly plundering of Ireland and Scotland, incursions made possible in no small part by the use of horses as an instrument of war.”

The need for pasture and water—coupled with the high profitability of sheeps’ hair and other animal “products”—was the basis for displacing other humans off of their own lands for primitive accumulation. The elites needed to force people to work the factories and emerging enterprises “processing” the enslaved animals that replaced them. The elite class appropriates the devalued peoples’ labor surplus and makes them buy the means of survival from those who have expelled them from their lands, with no power in the production process.

Modern day cow exploitation on a “dairy farm” (© Thomas Fries).

Modern-day chicken exploitation on an “egg farm” (CC2.0 Secretaria de Agricultura e Abastecimento do Estado de São Paulo).

As this constant and ever-sprawling expropriation happened throughout the world, it wasn’t only the search for water and pasture for domesecrated animals that was the reason for such enclosure and land-grabbing. In the 18th century, saladero industries used the domesicration and killing of animals to produce dried “salt-meat” which were then exported to feed enslaved humans in Cuba and Brazil. The enslavement and consumption of other animals made it not only possible but profitable to cross the seas and wage violent pillages and wars against other devalued peoples and species to build empires by abusing the labor and bodies of one oppressed group back to another.

The violent expansion of animal “farming” was fueled by demands from the “leather” and textile industries — industries that were financially backed by the British and American elite class. The growing profitability of such businesses fueled continuous domination from the West and the expansion of its influence, power and promotion of its incomprehensible levels of oppression and violence against humans and other animals.

A call for the abolition of animal use

It is no doubt that capitalism requires the exploitation of human labor, but as the status of nonhumans hardly surpass the status of a given “resource,” their victimization often goes unnoticed. Ultimately, we believe that such practices as confining, using, and eventually killing someone as a means to our ends, are violations of the natural rights they have. Yet we confine and kill trillions of other animals (land and aquatic) a year globally for “food” alone; kill thousands of free living animals at a time who would compete with humans who “farm” other animals; kill more animals in the name of conservation; kill even more other animals in the name of sport; kill still more other animals because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time, indiscriminately caught in hellish traps meant for a different species.

Other animals are viewed as mere production units with their very lives seen as wastage, an expense, inefficiency between input and output. And in the case for free living animals, they are competition, risk, unused resources more fit to adorn the walls, floors and bodies of human beings.

In Tom Regan’s The Case for Animal Rights, widely regarded as a classic of the animal liberation movement, Regan argues that nonhuman animals possess natural moral rights by virtue of being subjects-of-a-life. Animals are aware of this world and the things that happen to them, matter to them. Thus, they must be seen as ends themselves rather than as means to human ends.

Given this as an ideological basis, it becomes clear the depth of wrong in humanity’s pervasive, institutionalized usage of animals. Because the oppression of devalued humans is so intertwined with the oppression of other animals, dismantling the systems of hierarchies and capitalist–patriarchy requires consideration of the hierarchies and objectification imposed on other animals as well. As John Ballamy-Foster states in his book The Ecological Revolution, “a genuine ecological revolution, able to transform the relations between the mode of production and the ecology, would be associated with a wider social, not merely industrial, revolution, emanating from the great mass of people.” We have only been conditioned to see other animals as mere machines for human production, fit for tweaking, under “merely [an] industrial revolution” when we should challenge societal hierarchies down to its roots.

The very basis of veganism, anti-speciesism, and the resistance against using animals to serve human ends, is socialistic in nature. If we decided that other animals were to still serve us and our trivial desires, then their fate and the fate of their free-living cousins will not change. In fact, without the consideration and liberation of the other sentient beings we share this planet and have coevolved with, ecosocialism and sustainability would simply be a form of “green-washed human supremacy.”

Ultimately, we find the most value in other animals after we have killed them, so much so that their living period is treated as an inefficiency in production. Food and water go in one end and “steak”, milk, eggs and “pork chops” come out of the other end. Questioning this aspect of our social relations isn’t a new phenomenon; indeed people have been protesting the use, and inherent abuse, of other animals since the practice began. Though, throughout history those stories have largely been overlooked or erased like so many others in the age-old struggle against oppression.

The very basis of veganism, anti-speciesism, and the resistance against using animals to serve human ends, is socialistic in nature. If we decided that other animals were to still serve us and our trivial desires, then their fate and the fate of their free-living cousins will not change. In fact, without the consideration and liberation of the other sentient beings we share this planet and have coevolved with, ecosocialism and sustainability would simply be a form of “green-washed human supremacy.”

Ecosocialist advocacy must include the rights of all individuals who are affected by the impacts of supremacist ideology and capitalist expansion. Out of justice and not “compassion” or “generosity,” we must call to immediately abolish all use of animals. Ballamy-Foster argues that to see a change in human relation with the natural world, “the constitution of society at its roots within the existing social relations of production” must be radically challenged. Such a future can only be created in a collective struggle against oppression of all animals — human and nonhuman alike — that transcends the capitalist system.

Jessica Nicholson is a freelance artist, writer, researcher, animal advocate, permaculture enthusiast and a mother. Currently living in Massachusetts, her work revolves around animal and earth liberation as well as alternative food systems and ecology. She has her Associates of Arts in the curriculum of Arts and Science for sustainability studies from Holyoke Community College. To read more of her writing, visit startingattheroots.com or reach her at startingattheroots269@gmail.com.

Latest from Eon

- Abolition as a Project of Deep DemocracySince the police murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, a stunning uprising against state violence has spread to more than 2,000 American cities. As protests continue across the country from Seattle to Washington, D.C.—and even in smaller cities like Kenosha, Wisconsin and Stamford, Connecticut—the political momentum endures.

- On electoralism, grassroots power and disability justiceRead our conversation with Justin Farmer, a long-time community activist running for state senate in Connecticut.

- In defense of abolishing the policeCriminal justice in the US has evidently not shed itself of the violent racism and Christian theocracy out of which it was built and attempts to reform it are polluted by corporate interests. Abolition, on the contrary, can direct us towards creating models of real public safety.

If you enjoyed reading this, help support us by sharing it with others.