By Helena Carlson (first published in Current Affairs)

Since the police murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, a stunning uprising against state violence has spread to more than 2,000 American cities. As protests continue across the country from Seattle to Washington, D.C.—and even in smaller cities like Kenosha, Wisconsin and Stamford, Connecticut—the political momentum endures. Thanks to continuous direct action, decades-old conversations on police abolition have been revitalized, led by both the contemporary abolitionist and Black Lives Matter movements. Misguided efforts at police reform like #8CantWait—criticized for faulty data science, among other issues—have been countered by meaningful, explicitly abolitionist ones such as #8toAbolition.

Recent events like California Democrats’ rejection of mild police reforms and the Justice in Policing Act have made it clear that reforming the criminal punishment system is doomed to failure. To be sure, this has long been obvious: the prominent abolitionist Angela Davis has been speaking out against the failures of prison reform for decades. In her book Abolition Democracy, she stresses the need for a different criteria for democracy: one with “substantive as well as formal rights, the right to be free of violence, the right to employment, housing, healthcare, and quality education. In brief, socialist, rather than capitalist conceptions of democracy.”

Here, Davis is highlighting an older conception of democracy—one with uniquely American roots. As she says, “When I refer to prison abolitionism, I like to draw from the DuBoisian notion of abolition democracy. That is to say, it is not only, or not even primarily, about abolition as a negative process of tearing down, but it is also about building up, about creating new institutions.”

The term “abolition democracy” was originally coined by W.E.B. Du Bois in his highly influential book, Black Reconstruction. Abolition democracy describes the interacting politics of the labor and civil rights efforts during the Reconstruction Era following the Civil War, as well as the potential that abolition holds for transforming American democracy. As professor and sociologist Brendan McQuade writes in Lessons of Rojava and Histories of Abolition: “Abolition democracy challenged the fundamental class relations upon which historical capitalism stood: a racially stratified global division of labor, which, starting in the sixteenth century, tied Europe, West Africa, and the Americas together in a capitalist world-economy.” McQuade reiterates Du Bois, noting that the revolutionary moments of abolition democracy were briefly achieved during Reconstruction, powered by mobilizations and direct action of Black workers as well the temporary class alliances between Black workers, poor southern whites, middle class abolitionists, and northern industrialists.

Abolition democracy then, says Davis, is the “democracy that is to come, the democracy that is possible” through the continuation of the great abolitionist movements in American history and around the world.

But for such transformations to endure, they need to be planted in more fertile soil. “DuBois pointed out that in order to fully abolish the oppressive conditions produced by slavery, new democratic institutions would have to be created,” says Davis in Abolition Democracy. Du Bois’s observation—that abolition as a negative process on its own was not sufficient—deeply resonates with contemporary approaches to abolition democracy.

Abolition democracy then, says Davis, is the “democracy that is to come, the democracy that is possible” through the continuation of the great abolitionist movements in American history and around the world. Abolition democracy requires us to radically reimagine the institutions that shape our lives, and to take an active role in building them anew.

What would creating these new institutions look like? As grassroots abolitionist collectives like MPD150 have put forth, it would entail building a society that fosters collective life where everyone’s basic needs are met. It means engaging in policy work that prevents crime, rather than punishing it. Abolition necessitates the “transformation of the social conditions that perpetuate violence,” as described in the anarchist zine, what about the rapists? The writers argue for a reexamination of what we consider as “crime” and “justice.” In their view, we should understand these concepts within the context of power and systemic oppression, with an eye toward developing transformative models that offer genuine conflict-resolution and healing for victims.

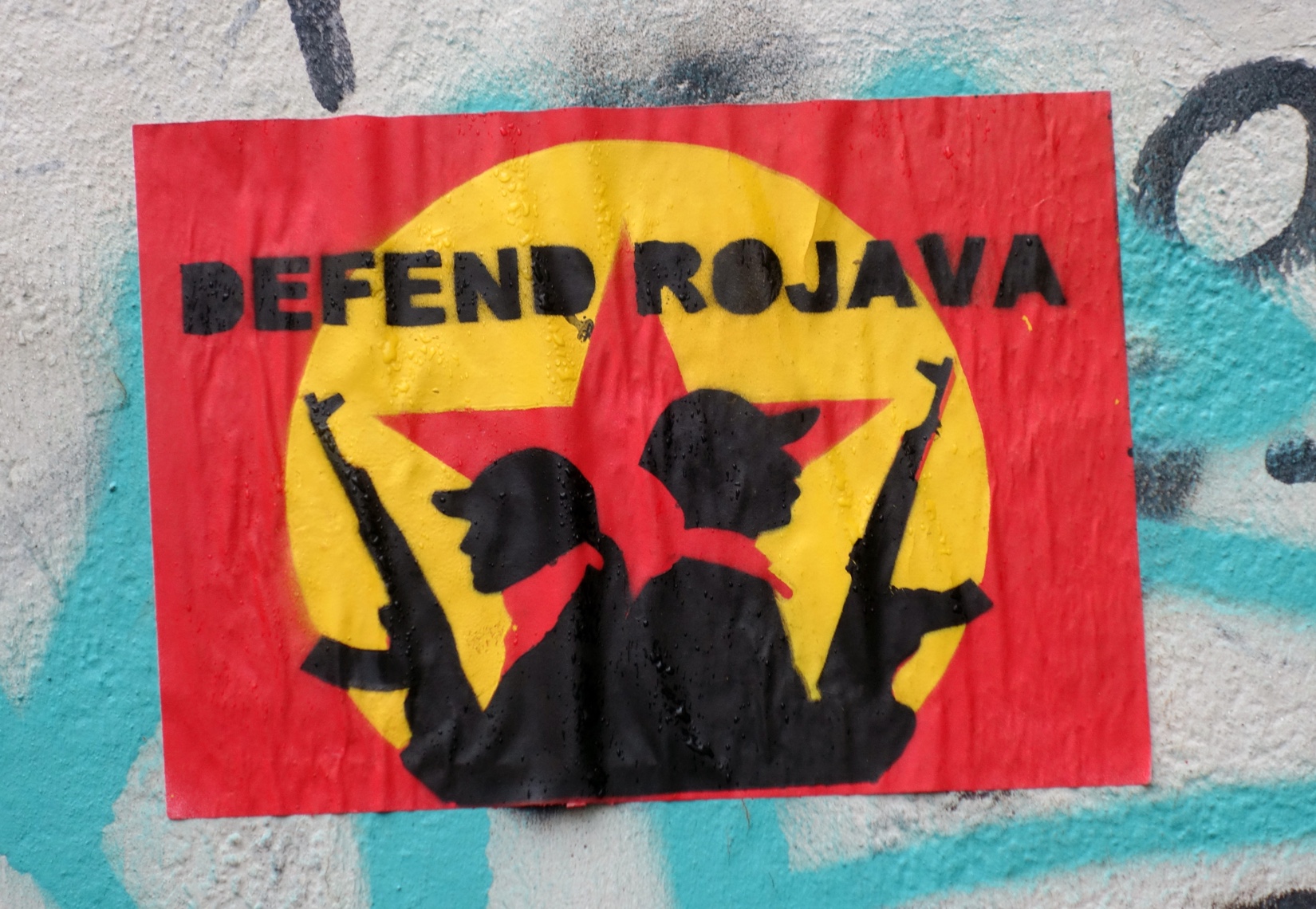

Prison abolition is often derided as idealistic or utopian, but it’s more achievable than some might think. In fact, decentralized communal defense models and widespread restorative approaches to justice already exist in Rojava, the Kurdish name commonly used to describe what is formally called North East Syria. As many activists have noted, this autonomous region in northeastern Syria provides a striking modern example of how democratic solidarity in resistance to growing authoritarian power worldwide can inform present-day political efforts within the United States.

“Not long ago, few observers could have foreseen the emergence of a democratic revolution in northern Syria, or even believed it could happen. So in the spring of 2011, when the Kurdish freedom movement declared its aim to build a society around a concept called ‘Democratic Confederalism,’ few noticed,” write Michael Knapp, Anja Flach, and Ercan Ayboga, co-authors of the book Revolution in Rojava: Democratic Autonomy and Women’s Liberation in the Syrian Kurdistan. The popular uprisings in July of 2012 that liberated Kurdish-majority cities and villages from the Ba’ath dictatorship were largely overlooked by the West, which was slow to realize that a remarkable contemporary revolution was taking place.

It wasn’t until January 2014, when the three cantons of Rojava, Afrin, Kobane, and Jazeera issued a declaration of Democratic Autonomy—or perhaps around a year later, when the coalition triumphantly defeated the Islamic State at Kobane—that “the world finally noticed,” as Knapp et al put it.

Originally born out of the movement to free Kurdish people from sustained repression, Rojava became a revolutionary project to build a society around what is called democratic confederalism. In a democratic confederalist society, a “social economy” is implemented and all resources, including factories, are collectively owned and self-governed through communes and cooperatives (this differs in obvious ways from the “market economies” that currently dominate the world, in which private actors vie for control over resources and influence). Against all odds, under global scrutiny and pessimism, the political structures of Rojava have functioned and endured at a level that has surpassed expectations.

But how did they first come into being? A little over 40 years ago, the Kurdish movement, catalyzed by the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) and its figureheads Abdullah Öcalan and Sakine Cansız, sought to free the Kurds from deep-rooted oppression in Turkey. As Knapp et al describe, anti-Kurdish racism had long been an integral part of Kemelism, the Turkish “modernization movement” that sought to stamp out Kurdish language and culture. However, Rojava’s vision has evolved beyond Kurdish independence, and today it encompasses culturally diverse communities, including Arab-majority regions liberated from Islamic State control. (The autonomous Rojava region is large and diverse, home to 4-5 million people from different ethnic and religious backgrounds, including Kurds, Arabs, Armenians, Turkmen, Syriac-Assyrians, Yezidis, Circassians, Chechens, and nomadic Dumi.)

Since its declaration of autonomy, Rojava has witnessed prolonged conflict in its violent campaigns against the Islamic State, other jihadist groups, and the ongoing Turkish invasion. Surrounded by rival nation-states, Rojava has also suffered from their imposed political and economic embargo. At the same time, thousands of both Syrian and international activists have flocked to the region in support of the movement and its unprecedented experiment in radical democracy and self-governance.

As Ercan Ayboga, co-author of Revolution in Rojava and a longtime activist in grassroots organizations like the Mesopotamian Ecology Movement, said in an interview with Current Affairs: “Democracy in our view needs active [contributions] from everybody. Each person in the society should be able to organize at the lowest level possible and take part in the decision-making process.”

In contrast, Ayboga said, a parliamentary democracy where elections are only held every four to five years opens up room for secrecy and corruption by powerful interests. A democratic confederal structure doesn’t preclude corruption, but minimizes it with continuous, active discussions among all members of society. In Ayboga’s view, “People become more aware of what’s going on and which decisions are being made. Everybody who takes part in discussions, even at the lowest level, should be able to make their proposal and discuss with others or request transparency.”

Continuous social engagement is a key component to democratic confederalism. It’s an essential element of abolition as well, since it helps sustain political awareness at the local level. Greater civic engagement can also make life more enjoyable in many ways by bringing together community members of all backgrounds and age levels.

“I like to go to the communes often to speak to people there. You could find a way to join meetings,” Ayboga said. “In the streets it was very relaxed to walk around. It was a nice atmosphere, quite peaceful, and you could go to every shop and speak to everybody.”

Rojava’s pursuit of deep democracy grew from a major shift in the ideology of the PKK and subsequently the Kurdish rights movement. The PKK, which had its roots in traditional Marxism and nationalism “much like many of the anti-colonial liberation movements of the second half of the 20th century,” evolved over time “in response to the profound failure of state based socialism as embodied by the USSR,” as Ayboga details in Revolution in Rojava.

By the early 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the movement experienced a paradigm shift away from the top-down Marxism-Leninist approach in favor of grassroots alternatives. This was to avoid reproducing patterns of oppression seen in capitalist and nation-state systems. Within a few years, the PKK largely gave up on the notion of building a Kurdish nation-state in favor of focusing on equal rights and Kurdish autonomy within the Turkish state.

Yet the movement didn’t give up the basic socialist vision of radical egalitarianism, Ayboga says. Rather, it embraced the idea of working at the given moment “wherever we are, whatever time it is” to develop alternative forms of governance within the existing state structures in Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran, where most Kurds resided. The PKK also actively collaborated with other Marxist-Leninist, Maoist, anarchist, and feminist forces, and was one of the ten revolutionary socialist organizations to form the Peoples’ United Revolutionary Movement—whose stated goal was to overthrow the “collaborative fascist AKP [Justice and Development Party] and TC (Turkish Republic) system of sovereignty”—in 2016.

The theories that guided the development of democratic confederalism can largely be credited to PKK figurehead Abdullah Öcalan, who to this day remains a political prisoner in Turkey. His life has been a distinguished yet turbulent one: on February 15, 1999, Öcalan was abducted in Nairobi, Kenya by Turkish intelligence forces with the help from the CIA. He was brought to Turkey and sentenced to death, which eventually was negotiated to a life sentence.

In his decades of incarceration, Öcalan has abandoned his former Marxist and Stalinist beliefs as he became exposed to social theorists like Immanuel Wallerstein, Fernand Braudel, Friedrich Nietzsche—and most importantly, liberatarian socialist Murray Bookchin. Bookchin’s concept of communalism, which places emphasis on collective ownership and “demands the formation of popular assemblies and their confederation,” heavily inspired Öcalan’s theories on democratic confederalism.

Both former Marxists, Bookchin and Öcalan have a dialectical approach to developing revolutionary theory. Yet instead of trying to predict an inevitable future revolt, they studied historical development “for ethics—to derive, from what has happened in the past, what ought to come next,” in the words of Janet Biehl, who co-edited the journal Left Green Perspectives with Bookchin. Thus, Öcalan’s solution to freedom for the Kurdish people hinges on a sort of libertarian municipalist revolt: abolishing the nation-state system under which racial and patriarchal violence proliferate. There could be a number of different means to this end, whether through a Marxist-Leninist vision of a “cataclysmic revolution” or one of “transcendence” as conceived by Öcalan. The latter requires cultivating a deeper, more authentic form of democracy—the type that is envisioned by contemporary advocates of abolition democracy.

Such a transformation doesn’t happen overnight, or by accident. In fact, one of the biggest challenges facing activists in Rojava—and in the United States, or anywhere else for that matter—is what activists described as a “lingering state mentality” where people are not accustomed to seeing themselves as part of the political process. Building a participatory-democratic approach to politics, whether as part of the struggle here in the United States or in Rojava, is not only done through a pure installation of new political and economic structures. Instead, as Öcalan writes, it requires a society “to [institutionalize] the communal and democratic identity.”

Both former Marxists, Bookchin and Öcalan have a dialectical approach to developing revolutionary theory. Yet instead of trying to predict an inevitable future revolt, they studied historical development “for ethics—to derive, from what has happened in the past, what ought to come next,” in the words of Janet Biehl, who co-edited the journal Left Green Perspectives with Bookchin. Thus, Öcalan’s solution to freedom for the Kurdish people hinges on a sort of libertarian municipalist revolt: abolishing the nation-state system under which racial and patriarchal violence proliferate.

To understand what this means in practice, it’s helpful to look at a concrete example. In Rojava, communes are the basic level of social organization—these are then federated into people’s assemblies and people’s congresses focused on specific issues, like women’s liberation, multiculturalism, and ecological consciousness through economic systems that collectivize natural resources and land. Each of these groups are aimed at helping members develop a deeper personal understanding of the issues at hand: some women’s assemblies, for example, hold workshops where attendees can discuss books on the topic and explore its role in the revolutionary agenda.

This type of active participation is essential to democratic confederalism. As Öcalan puts it in his book Democratic Confederalism, “Each community, ethnicity, culture, religious community, intellectual movement, economic unit, etc., can autonomously configure and express themselves as a political unit.” To him, democratic confederalism is a simple and implementable tool “with which to [politicize] society” and overcome the problems originating from the nation-state system.

Overcoming those problems requires more than a nostalgic retreat to “simpler times.” It demands that we imagine new ways of relating to each other—and the umbrella women’s movement in Rojava is a prime example. Rather than merely returning to an antiquated model of local patriarchy, Rojava has made efforts to address the systemic inequalities faced by women, and to ensure that women are represented and protected. A comprehensive 2019 report conducted by the Rojava Information Center (RIC) notes that while there have been “challenges in establishing a shared vision and practice of women’s liberation across all of society,” there have also been “numerous tangible successes” like the establishment of the Women’s Economy Committee of the Autonomous Administration and Kongreya Star which has helped create women’s cooperatives and supported women in developing skills to become financially independent. In addition, “Women’s Houses” were established throughout cities in Rojava dedicated to addressing gender-specific issues such as domestic violence, marriage and divorce, and oppression within family structures.

In order for the system to sustain itself, however, the report says, addressing tensions between the Kurd and Arab populations (and minority Assyrians) is crucial. There’s been some progress on this front: as noted in the RIC report, work has been done to bring together community leaders of different ethnic and religious backgrounds across the autonomous region. Despite challenges, numerous achievements have been made to improve the general standard of living. This includes standardizing the multilingual education system, providing people with bread and diesel through the commune system, and creating cooperatives that help empower people to open small businesses.

While Rojava does still have prisons—they’re part of the criminal justice institutions inherited from the state—the vast majority of social disputes are resolved at the commune level between involved parties where even a single member can obtain the dismissal of a top official. The death penalty has been abolished, and detentions and custody locations can be openly accessed, as Human Rights Watch has confirmed. The overall justice system has been re-oriented towards re-socialization and education, writes Knapp et al, and once the means are available, the aim is that prisons will be transformed into rehabilitation centers.

“The wish of the revolutionary society, at least in Rojava, is that there shouldn’t be the need to resort…to a judge nor to a people’s jury, nor to muster hundreds of people in order to evaluate if a person is guilty, and ask the attorney for how long the person will have to stay in prison,” writes Italian journalist Davide Grasso in Rojava: Has Revolution Eliminated The State?

In the communes where people know and are more trusting of one another, conflict resolutions can be made in the majority of cases. “The communes are thought out ‘against’ the boards at the top: they limit their power and exert in turn a power from below, which is predominant compared to the one coming from above. This is the difference from the state system,” explains Ghalia, a member of the Amude People’s House in a conversion with Grasso.

Communes are also where laws are proposed for the region’s legislative board and where volunteers are selected for the civilian defence forces (HPC) who organize at the municipal level, intervening in violent conflicts, patrolling neighborhoods and guarding public buildings and events. They are not entirely unlike police, but each person, including women and seniors, is encouraged to volunteer in the HPC through a roster system. This more decentralized model of communal security, explains Kurdish academic Hawzhin Azeez, reduces the possibilities of authorities monopolizing power. The HPC supplements the Asayish, the region’s professional security forces whose predominant role are to man checkpoints between cities and contain intelligence services and anti-terror units in response to foreign attacks.

Despite these successes, it’s an unfortunate fact that Rojava’s remarkable experiment in radical democracy is likely near its end. In October 2019, the United States terminated its alliance with Rojava, essentially clearing the way for Turkish invasion of the region. Yet the possible end of Rojava does not mean that it is a failed project—or that we can’t apply its lessons in the United States, however different the political context may be.

Advocates of democratic autonomy are well aware that there’s no one-size-fits-all solution to the world’s current political woes. “Öcalan, and our movement—the Kurdish freedom movement—proposes democratic confederalism to the four states where the Kurds live, but we don’t claim that democratic confederalism is the solution,” Ayboga said. “We say that for the Middle East, it is an option. In every state, region or country, the implementation of democratic autonomy of course is different given the different conditions. At the global level, [democratic confederalism] can be a contribution to the search for democratic alternatives, to develop a more democratic society free of patriarchy, class structures, ecological destruction, exploitation and so on—that’s a big aim.”

While the term “democratic confederalism” might sound strange to American ears, its principles of communal identity and widespread political education are not new. Rather, they have much in common with the ideas that have animated decades of struggle for racial and economic justice in the United States. We can see similar principles at work when we examine the legacy of the Black Panther Party, whose chapters across the nation advocated a 10-point socialist program and launched social projects like the Free Breakfast for Children Program, which expanded to providing medical and legal support in Black communities.

Nor do we have to look solely to the past to imagine what deep democracy might look like in the United States. Ambitious projects like the Jackson-Kush plan put forth by the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement are examples of the municipalist endeavours taking root in recent years. Its aims—to build people’s assemblies, an independent Black political party, and a broad-based solidarity economy—share similar ideological undercurrents that inspired the Kurdish freedom movement.

Revolutionary leaders, like Öcalan himself, have generally recognized that politics must become a part of daily social life. Each of us must commit to a continuous, inclusive vision of society where we can work as political actors ourselves at the grassroots level. And while Rojava is not an anarchist utopia, completely free of prisons, police, and state violence, its movement, as Grasso emphasizes, is one that “neither should be uncritically accepted nor arrogantly dismissed but considered useful for all those articulating a critique of the state.”

As Fred Moten and Stefano Harney write in their critical essay, The University and the Undercommons, “[Abolition is] not so much the abolition of prisons but the abolition of a society that could have prisons, that could have slavery, that could have the wage, and therefore not abolition as the elimination of anything but abolition as the founding of a new society.”

Abolition, based on principles of communal solidarity and informed by both historical and international struggles for deep democracy, is a vital tool for building and sustaining models of self-direction. It provides one of the best available frameworks for fostering internal peace and tolerance. Ultimately, abolition—and the deep democracy essential to its functioning—may be the only way to transcend the exploitation that arises from capitalism.

Featured image by txmx-2 licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Latest from Eon

- Abolition as a Project of Deep DemocracySince the police murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, a stunning uprising against state violence has spread to more than 2,000 American cities. As protests continue across the country from Seattle to Washington, D.C.—and even in smaller cities like Kenosha, Wisconsin and Stamford, Connecticut—the political momentum endures.

- On electoralism, grassroots power and disability justiceRead our conversation with Justin Farmer, a long-time community activist running for state senate in Connecticut.

- In defense of abolishing the policeCriminal justice in the US has evidently not shed itself of the violent racism and Christian theocracy out of which it was built and attempts to reform it are polluted by corporate interests. Abolition, on the contrary, can direct us towards creating models of real public safety.

If you enjoyed reading this, help support us by sharing it with others.